Deanna Soloninka, PhD candidate in Politics at Edinburgh University

For researchers of political and institutional change, path dependency matters. Outcomes can be traced back. Findings from a detailed analysis illustrate that “countries move along (nationally specific) well-worn paths” (Thelen 1999, 394). Studies of regional and international organizations catalogue similar pathways scaled up. Because policymakers work from existing templates, new institutional forms relate back to starting conditions. And while exogenous shocks have the power to influence the political trajectories of states and organizations creating space for substantive reform, change is not guaranteed. All these considerations coalesce when mapping the origin, impact, and potential of the European Union (EU) Commission’s Support Group for Ukraine (SGUA).

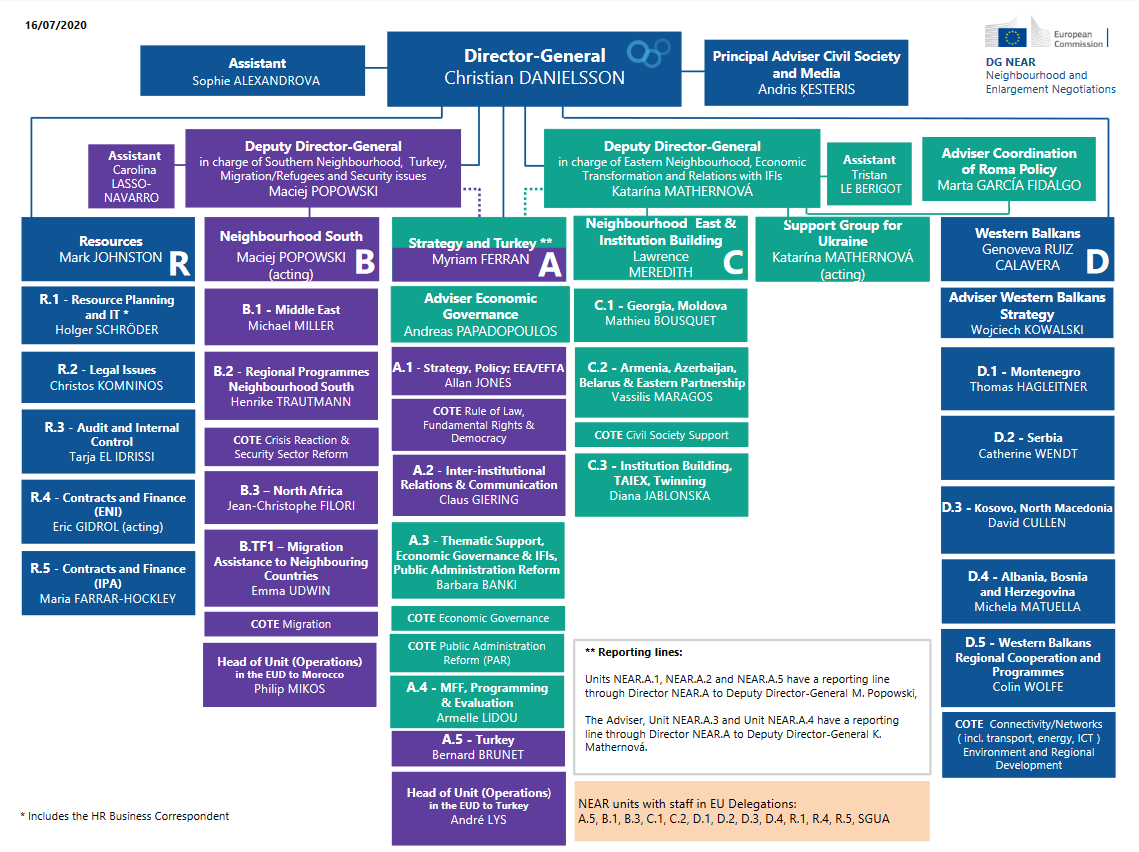

The Brussels-based SGUA was unveiled in April 2014 by European Commission President Barroso to “provide a focal point, structure, overview and guidance for the Commission’s work to support Ukraine”. The role of the SGUA in coordinating assistance and financial support is combined with facilitating the implementation of the Association Agreement (AA) with the EU, and direct participation in reforming the basic structures of the Ukrainian state. Despite this impressive mandate, the SGUA remains a somewhat enigmatic participant in EU-Ukraine relations: highly regarded yet not well known, unique and innovative while at the same time resembling other EU instruments and challenged by some of the same shortcomings identified in previous forms of EU engagement with third countries. In a Chatham House expert comment last year, Kataryna Wolczuk observed that even within the EU, current officials may not fully appreciate the new mechanisms involved in EU relations with Ukraine following the Euromaidan. This is striking given the literal visibility (see Figure) of the SGUA—a key EU innovation in relations with Ukraine—in the organizational architecture of the Commission’s Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR).

Figure. Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR). Source: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/near-org-chart.pdf.

Figure. Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR). Source: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/near-org-chart.pdf.

From the EU itself to Ukraine as a country in the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), to Ukraine’s AA signed in 2014 and within it the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), many actors and aspects of EU-Ukraine relations have been designated unique. The SGUA does share points of tangency with the Task Force for Greece (TFGR) which supported similar institutional reforms from 2011-2015. And interestingly, the two task forces have also included Peter Wagner: previously an advisor to the TFGR, and subsequently Head of SGUA as of 2016. Above all however, the SGUA is considered unique precisely because Ukraine is the only non-member country to receive this level and form of comprehensive support. There is for instance, “little evidence that the instruments developed for the Western Balkans were transferred directly to Ukraine” (Wolczuk 2019, 748). And yet, we do see continuities between elements of the SGUA in EU relations with other third countries, and with the ENP and Eastern Partnership (EaP) in Ukraine before 2014, especially concerning the centrality of technical assistance. What delineates the design and activities of this task force from these other forms of support is the way the SGUA’s work directly advising, coordinating, and facilitating has further stretched the definition of “international institutions as policy advisors” (Fang and Stone 2012, 537).

Like other aspects of EU external influence on non-member states, the SGUA remains understudied. However, piecing together the group’s trajectory reveals productivity despite a slow beginning. Indeed, while the establishment of the SGUA was referred to as ‘symbolic’ in a 2015 Jacques Delors Institute Berlin policy paper, by 2018 the task force was recognized as playing an essential role in Ukraine’s integration and reform efforts. Although the coordination of external support has made a significant difference to the delivery of assistance, the Head of SGUA emphasizes reform of the public administration as a central focus in terms of recruiting and developing domestic expertise to address long-running governance problems. There are also specific areas where the SGUA can improve. A detailed evaluation of EU assistance in 2018 emphasized the need for even more collaboration between the SGUA and the EU delegation in Kyiv in terms of project oversight, and ensuring the task force’s expert knowledge on EU institutions is matched by an equally comprehensive knowledge of local conditions. This latter problem is exacerbated by the typically short periods of time experts are seconded to task forces (Wolczuk and Žeruolis 2018). Ultimately however, the success of the SGUA will continue to depend overwhelmingly on Ukrainian political will.

Cautious optimism about the reforms the SGUA is guiding to fruition in Ukraine raises the question of replication elsewhere in the European—and especially eastern—neighbourhood. Using the group as a model for Georgia and Moldova was proposed during the original launch of the SGUA in 2014, and has been reiterated since. In 2019, Polish diplomat and Minister Jacek Czaputowicz explicitly called for the creation of a support group for Moldova to better sensitize the provision of EU assistance to domestic conditions. However, all planning associated with EU external relations has been fundamentally altered by the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. In April 2020, Peter Wagner announced on Twitter he would be stepping away from his post as Head of SGUA to support the Commission’s response to Covid-19. The SGUA is now being led on an interim basis by Deputy Director-General for Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations Katarína Mathernová. While this shift has been accompanied by encouraging indications of a continuity of focus on Ukrainian reform and occurred simultaneously with flows of EU emergency support to EaP partner countries to respond to the crisis, even prior to the pandemic Ukraine was one Commission priority among many.

‘Quiet politics’ flourishes when the focal points of contention are at the same time highly technical but of low political salience. This formula may help us better understand the work and reputation of the SGUA. Both in quiet politics and the task force, “superior knowledge of the terrain and access to key decisionmakers are the most valuable resources” (Culpepper 2010, 4). The SGUA has no expiry date in recognition of the long timelines associated with systemic state reforms. Conversely, as with all forms of assistance, enduring pressures to demonstrate progress combined with current levels of extreme uncertainty may inhibit the SGUA realizing its objectives in the coming years. Either way, the changes stimulated in both Ukrainian and EU ‘domestic’ politics since the Ukraine crisis began have already shifted political trajectories, however incrementally, while the SGUA itself further tests the limits of Ukraine’s integration without membership.

Deanna Soloninka is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

References

Culpepper, Pepper D. 2010. Quiet Politics and Business Power: Corporate Control in Europe and Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fang, Songying and Randall W. Stone. 2012. “International Organizations as Policy Advisors.” International Organization 66(4): 537-569.

Thelen, Kathleen. 1999. “Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science (2): 369-404.

Wolczuk, Kataryna. 2019. “State building and European integration in Ukraine.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 60(6): 736-754.

Wolczuk, Kataryna and Darius Žeruolis. 2018. “Rebuilding Ukraine: An Assessment of EU Assistance.” Chatham House Research Paper, London: The Royal Institute of International Affairs, Ukraine Forum. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-08-16-rebuilding-ukraine-eu-assistance-wolczuk-zeruolis.pdf.