Luke March

In-Depth Analysis

In the economic and financial crisis and its aftermath, European radical left parties have achieved some electoral success, though major challenges will continue to limit their prospects, writes Luke March. He argues that left parties have a difficult balance to strike between maintaining their principles in their policies and recognising the realities of current mainstream politics.

Syriza Greece March London, Ben Folley, CC-BY-2.0

2015 was the best year for the European radical left since the collapse of communism. In January, the stunning victory of the Greek Syriza ushered in the first declaratively anti-austerity government in the EU. In September, the radical socialist Jeremy Corbyn secured the leadership of the UK Labour Party, formerly the bastion of ‘Third Way’ social democracy. In December, the neophyte movement-party Podemos came third in the Spanish general elections.

Less noticed, the Portuguese radical left (Left Bloc and Communist Party) rounded out the year by supporting the Socialist government in November, marking the first time since the 1974 Carnation Revolution that the radical left had participated in government. Such events led many to believe that the left could finally aspire to proactively reshaping the European continent, finally undermining TINA (Thatcher’s adage that ‘There is No Alternative’ to neoliberal transformation).

What a difference a few months make! After holding out for a decidedly non-radical programme of greater state spending and debt forgiveness, the Syriza government caved in dramatically to ‘fiscal waterboarding’ from the Eurogroup. It is currently implementing an even more savage austerity package, showing that TINA is alive and well. While it renewed its mandate in September 2015, current opinion polls indicate it will do well to hold on to two-thirds of that vote. In June 2016, the Unidos Podemos coalition lost over a million votes and three seats, while, although Jeremy Corbyn trounced his challenger in September 2016, Labour’s opinion poll ratings remain dire.

But, just as 2015’s promises to change the continent were exaggerated, 2016 is hardly going to amount to the demise of the European radical left. That said, after a relatively favourable period when the radical left has benefitted, even if only marginally, from the Great Recession, it is likely that European radical left parties (RLPs) will face increased obstacles in the medium future, particularly as European economies move from more acute conditions to more chronic, low-level ailments, and the EU confronts complex crises which pose challenges to the left, not least the refugee and Brexit crises.

Today’s Radical Left – The ‘Mosaic Left’

Today’s European radical left is a ‘mosaic left’ – variegated parties and movements from motley backgrounds. Some are long-standing communist parties (reformed or reconstructed); some descend from Trotskyism or Maoism. Most are new coalitions that fuse formerly competing traditions (Trotskyist, Marxist-Leninist, New Left, social democratic, ecologist, etc).

Indeed, major efforts over the past two decades have gone into bridging chasms between former ideological enemies, both in forming new electorally-focused parties and in strengthening European nuclei of common action (eg the GUE/NGL European parliamentary group and the European Left Party). To the degree that there are now many common policies, resilient electoral parties and that the most sectarian and/or extreme parties are confined to the margins, this has been successful. To the degree that the radical left still has identity issues, is fissiparous and has few substantive policy achievements, there is still much to do.

What then do European RLPs stand for? The ‘radical’ appellation denotes an orientation towards ‘root and branch’ transformation of political and (particularly) economic power. They are ‘left’ in their commitment to egalitarianism and internationalism. In short, RLPs want greater democracy and are anti-capitalist. In practice, the situation is more complex, because many parties confine such anti-capitalism to mere anti-neoliberalism (which implies that there is a better form of capitalism).

Moreover, their radicalism is relative: both to the political system in which they are located, and to other political forces. They call for an interventionist state ameliorating poverty, inequality and exclusion (eg via re-nationalisation and high minimum wages) and for the reconstruction of international economic and military power (eg abolition of NATO and growth-oriented policies within the EU). Many of these policies are less radical than those promoted by formerly mainstream Keynesian social democrats, certainly than those the UK Labour Party promised in 1983. It is a sign of how TINA has taken hold that essentially social-democratic policies are now seen by the mainstream as ‘far left’, the post-2008 crisis of neoliberalism notwithstanding.

To reduce RLPs’ policy offerings to reheated social democracy is simplistic, not least because they have other components (eg greater emphasis on extra-parliamentary mobilisation, grass-roots democracy and alter-globalism), but it does indicate the fundamental identity issue at their core. Today’s RLPs have flourished in large part because they claim to be the ‘real left’, appealing to disaffected social democrats whose parties neoliberalised under the influence of the Third Way.

But can these parties move from being essentially a protest group within social democracy (a tradition itself in near-terminal crisis) to a force able to transcend social democracy, incorporate it and yet attract new constituencies? That remains the key problem, acknowledged by Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias:

We are not opposing a strategy for a transition to socialism, but we are being more modest and adopting a neo-Keynesian approach … calling for higher investment, securing social rights and redistribution. That puts us on a difficult terrain open to the standard criticisms of neo-Keynesian claims.

Electoral Performance and the Crisis

Whether today’s radical left is in a good position depends on perspective. On one hand, electoral performance (7.2 per cent on aggregate in the 2010s) has recovered, but is still below 1980s levels (9.3 per cent) – these following decades of decline. The European radical left no longer exists as a movement in the pre-1989 sense, with (albeit in few European countries) strongly institutionalised parties embedded in subcultures with a panoply of affiliated social organisations. There is no Soviet Union as a revolutionary alternative, and the main RLPs are ‘left reformist’ parties with weak social bases incapable of exploiting class discontent.

On the other hand, although the radical left has undoubtedly critically weakened in several of its former bastions (eg France, Italy and the Nordic countries), it has become more diverse and geographically spread. The USSR’s demise has allowed parties to adapt to national conditions more dynamically. In some countries (eg Austria and the UK), there remains no parliamentary radical left, but in others, new RLPs are able to reach levels of support unattainable in the late Soviet era (eg the Netherlands, Germany, and Iceland).

Since the Great Recession, a number of smaller parties have entered national politics for the first time (eg in Ireland and Belgium), and even in East-Central and South-Eastern Europe, which for historical reasons have been a radical left vacuum since 1991, there are signs of newer movement-parties able to articulate protest sentiments (eg in Bosnia, Croatia and above all Slovenia, where the United Left broke into parliamentary politics in 2014). In Poland, the Razem (Together) party also nearly entered parliament in 2015.

On balance, however, the Great Recession has proved to be a very mixed blessing for the radical left. In a newly published volume, including contributions from many European specialists, Dan Keith and I discuss this in depth. In aggregate, the post-2008 period has produced a demonstrable uptick in electoral support, with a near-60 per cent overall increase in votes (albeit usually from a low base).

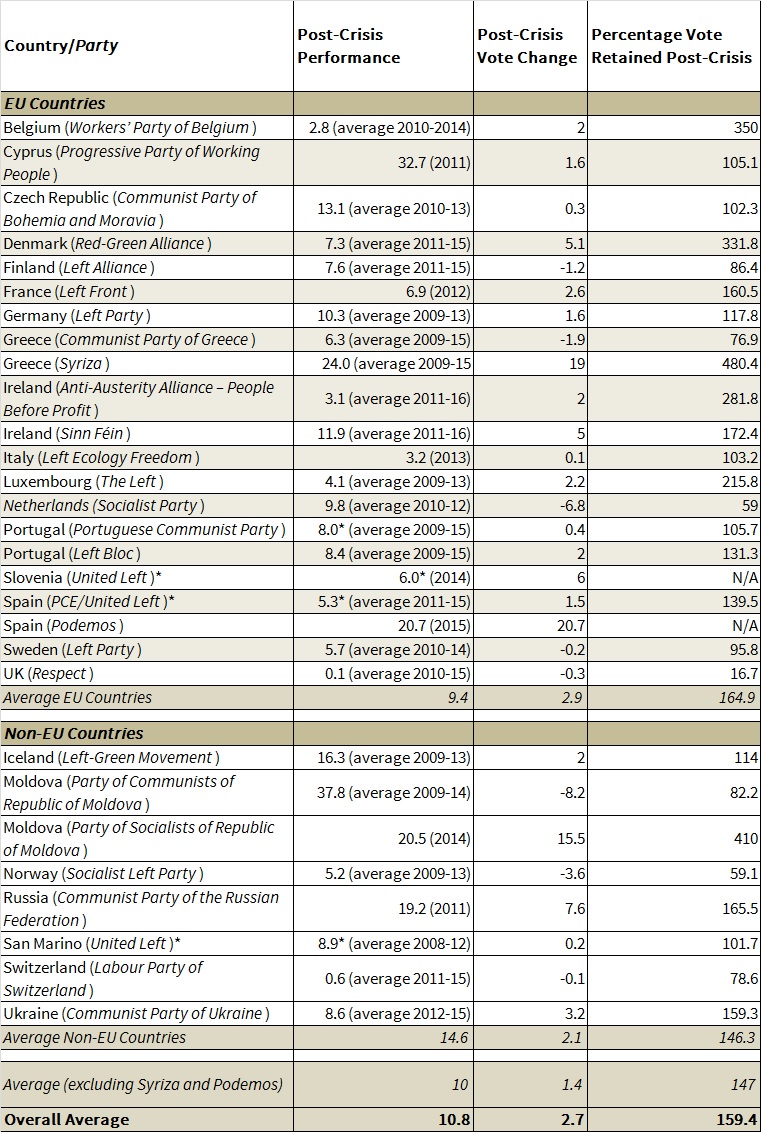

Key: * Coalition. Calculations from Parties and Elections in Europe. Parliamentary parties only.

Key: * Coalition. Calculations from Parties and Elections in Europe. Parliamentary parties only.

Figure 1 | European Radical Left Parties’ National Electoral Performance (September 2008-April 2016)

Nevertheless, the table above indicates how much of the growth is made up by a few parties (Syriza and Podemos above all). Even some of the larger, more established parties such as the German Die Linke and Dutch Socialist Party have struggled to increase their perspectives during the crisis. Overall, the radical left still tends to do better in poorer and/or smaller countries, and is regularly dwarfed by the radical right in some of the more prosperous/larger countries (eg France, Italy and the UK).

Our research identifies several reasons for the general failure to benefit from the crisis. Above all, both the socio-economic crises and radical left responses have been very nationally-specific. Both a significant economic and political crisis and an astute party response are needed for success. Not coincidently, the best performances (eg Greece and Spain) have come in countries hardest hit by the crisis, where the establishment has been substantially delegitimised, where the left has a lot of residual legitimacy because of its anti-dictatorship history, where social protest has been most mobilised, where the radical right does not (yet) play a significant protest role, and where the left has adopted new approaches (eg populism combined with a pragmatic approach to government).

In other cases (eg the Netherlands and Germany) the socio-economic crisis has been much less marked, while in other countries (eg Ireland and Latvia), sectarian approaches from the left have limited its ability to benefit. In other cases still (eg Iceland and Cyprus), the radical left has governed through the crisis and its substantive performance has been found wanting.

Above all, though, the Great Recession was a capitalist crisis and not a terminal crisis of capitalism and neoliberalism, though bloodied, remains unbowed. Moreover, RLPs still lack strategic approaches to overcoming neoliberalism at European level, because, although they increasingly coordinate tactics and policies within pan-European bodies, they still fundamentally disagree on how to relate to the EU long-term: is it an unreformable capitalist conspiracy or a multilevel system amenable to resisting neoliberalism with internal pressure from the left?

Long-Term Challenges for RLPs

The most acute symptoms of the crisis are now receding, not least because a radical left party is tasked with managing policy in the Eurozone’s weakest link. Although high unemployment, inequality, low growth and a debilitated political mainstream will continue to give RLPs growth potential, the economic crisis is now being superseded by others, principally the refugee crisis and the Brexit crisis. Although it is currently impossible to see how these will pan out, there are three interrelated and long-term reasons why RLPs may struggle to build on its incremental growth in recent years.

First is that, despite its increasing pragmatism, the radical left remains one of the most ideological party families, with a core of principles (eg anti-militarism, internationalism) that are reflected in often comparatively rigid policy proposals (eg opposition to all privatisation, unfettered immigration, no military intervention). The right, in contrast, tends to be more about values and identity than programme (eg nationalism, traditionalism).

This makes it more flexible and adept at ‘redwashing’ (ie adopting the left’s policy agenda). For instance, Angela Merkel, combines ordo-liberalism with advocating a financial transaction tax, one of the radical left’s favoured policies. Our research has shown how most RLPs have remained uncritically pro-immigration, even when this has put them very firmly against the tide of public opinion.

Unfortunately, paranoid nationalism currently makes better politics than idealistic internationalism. This is not to decry principled politics, merely to note that the left is (generally) far less equipped than the right to appeal to emotions, identity and fears, as noted by George Lakoff in his analysis of the Democratic Party (Don’t Think of an Elephant). This has recently implicitly been acknowledged by Podemos and Syriza, in their self-description as ‘patriotic’ forces. The other flipside of staunch principles is that it is very damaging when they are renounced. Parties such as Syriza and the Cypriot AKEL have had to enact the very policies that the opposition to which was previously their raison d’être.

Second is the radical left’s problem in transforming from articulators of social protest to government. They have long decried the social democrats for their inordinate compromise and for accepting TINA, often arguing that social democracy is dead as a radical force. At the same time, they face a fundamental credibility problem (exaggerated by mainstream media), since there is simply no example of successful radical left government in a major European state.

RLPs have become increasingly orientated towards governmental coalition, and have achieved some notable piecemeal results (eg implementation of progressive taxation in Iceland in 2009-2013), but they have generally been the handmaidens of larger social-democratic parties, and have usually suffered electorally as a result.

There are three occasions where the radical left has led a European government in the last decade (Greece, Cyprus and Moldova). In no case has their governing record been substantially different from that of a left-leaning social-democratic government. As for Syriza, a recent party report damned its governing record to date. Until such time as RLPs can demonstrate a distinct governing offering, they will find it difficult to convince supporters and detractors alike that they are not better off in permanent opposition.

Third is that the radical left often still has an economistic vision that underestimates the political aspects of power. Syriza and Podemos are principal exceptions, with their trenchant critiques of the political elite (‘oligarchy’ and ‘caste’). But the fact that this is true in many other cases can be seen in their attitude to the EU. The radical left’s European parliamentary forces are weak, but their inability to agree on whether to reform or undermine the EU from within means that their parliamentary group (the GUE/NGL) and transnational party (the European Left Party) are even weaker than their size suggests.

Similarly, the preference of some of the left for ‘Lexit’ (left exit from the EU) is predicated on the idea that the EU is an imperialist, authoritarian agglomeration of capital, which can only be dissolved not reformed. As Brexit indicates, this completely ignores that the EU is still intergovernmentalist rather than genuinely supranational, and therefore its break-up is much more likely to reinforce interstate tension, anti-immigration sentiment, nationalist autarky and the marginalisation of the left than any supposed ‘socialism in one country’.

The State of the Left: The UK’s Labour

All the above tendencies promise a difficult few years for the left. The example of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour is the exception that may prove the rule. On the face of it, the Corbyn phenomenon has more in common with Bernie Sanders than other radical left forces, inasmuch as, instead of forming new left movements, anti-establishment anger has been directed to steering the mainstream centre-left away from neoliberalism, ‘changing the conversation’ and refounding a more genuinely leftist party that reinvigorates new constituencies with an anti-establishment leader and astute use of social media.

On the face of it, Corbyn has been much more successful than Sanders, seizing the Labour machinery and becoming, as Opposition leader, a genuine prime ministerial contender. But Labour now suffers acutely from the three weaknesses of the radical left identified above: over-ideologisation, over-dependence on protest and underestimation of politics. These perhaps pale compared with its cardinal weakness: that an ‘outsider’ candidate with a radical agenda presides over a profoundly electoralist, centrist and non-radical party, most of whose Westminster MPs distrust him and do not share his vision. However, they are major obstacles in overcoming this organisational conundrum.

Corbyn represents an authentic, non-mainstream politician, someone with principle, strength and integrity. As a serial rebel, he has never done compromise and stands in stark opposition to the New Labour record of increasingly technocratic, illiberal and neoliberal government. He represents a welcome return to values-based politics after Labour’s increasing identity vacuum (accelerated by its support for the Iraq war and failure to offer an economic alternative during the crisis).

The flipside of this is that his more ardent supporters now reject the Blairite record wholesale (despite him being Labour’s most electorally successful leader). Labour now witnesses a marked upsurge in sectarian politics, with Corbyn critics accused of being ‘Red Tories’ or worse, and proposals to deselect his Westminster critics as ‘traitors’.

Second, Labour has been redefined as a movement, particularly through the efforts of the pro-Corbyn Momentum movement. This has led to a new emphasis on reinvigorating and democratising its mass membership (which has increased by nearly 350000 since 2015 to become, allegedly, the largest party membership in Western Europe). At the same time, whereas previously Labour often appeared to pursue ‘electability’ for its own sake, now electability is decried with a turn to prefigurative politics.

Labour, it is said, does not need a traditional leader and should concentrate on finding a new identity, even before offering it to the electorate. Corbyn’s lack of support among his parliamentary colleagues (who in summer 2016 voted no-confidence in him by a 172-40 margin) was dismissed because of his overwhelming membership support and because of the party’s new anti-establishment ethos.

The Corbyn strategy might conceivably work with a more proportional electoral system, if Labour was simply another Podemos or Syriza, where the UK establishment had similarly collapsed, but its final weakness is that it completely ignores political constraints, such as an electoral system that forces Labour to appeal to centrist voters in southern constituencies, a parliamentary democracy with a strong leader focus, etc. Above all, it ignores consistently terrible polling ratings in the wider electorate and the swift reconstitution of the Conservative Party post-Brexit. Although his leadership re-election has temporarily quelled obvious disquiet, Corbyn leads an increasingly electorally marginalised and split party.

The UK example is obviously in many ways specific, and, as the UK leaves the EU, is unlikely to impinge much on the wider European radical left. But it does illustrate some lasting challenges that I have identified throughout: the need for new identities that are not simply parasitic on a decaying social democracy, the need to blend electoralism with immersion in social movements and to strike the right balance between principle and pragmatism. So far, most radical left parties have managed to address these issues fleetingly, if at all.

This article was originally published in the newsletter of the European Politics and Society Section of the American Political Science Association and is reproduced with the permission of the publisher.

Luke March

Luke March

University of Edinburgh

Prof Luke March is Professor of Post-Soviet and Comparative Politics and Deputy Director of the Princess Dashkova Russian Centre at the University of Edinburgh. His latest book, edited with Dan Keith, is Europe’s Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream? (RLI, 2016).

Shortlink: edin.ac/2eFLagH | Republication guidance

Please note that this article represents the view of the author(s) alone and not European Futures, the Edinburgh Europa Institute or the University of Edinburgh.

This article is published under a Creative Commons (Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International) License.

This article is published under a Creative Commons (Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International) License.